Introduction

This post identifies and presents the naming patterns of airlines. It also serves the purpose of rendering a large number of coloured rectangles.

Notes

The raw notebook can be found here. The scripts invoked therein are deposited in this repo.

Data

Data source

The airline names were collected from the flightradar database. The html page was scraped with the magificent lxml parser to obtain the individual names.

Data Preparation

Cleaning

All names were sanitised by casting them as lower case, removing terminal non-printing characters. The medial non-printing characters were replaced by a single space.

Censoring

Only the names of airlines operating regular flights accessible to the general public were retained. Charter airlines, jet services, flight schools and other flight operators not fitting the criterion were thus eliminated. This was done by programmatically matching tokens, such as private, school in the names. The resultant collection were then once more cleaned manually to discard the few remaining spurious entries.

Analysis

Components

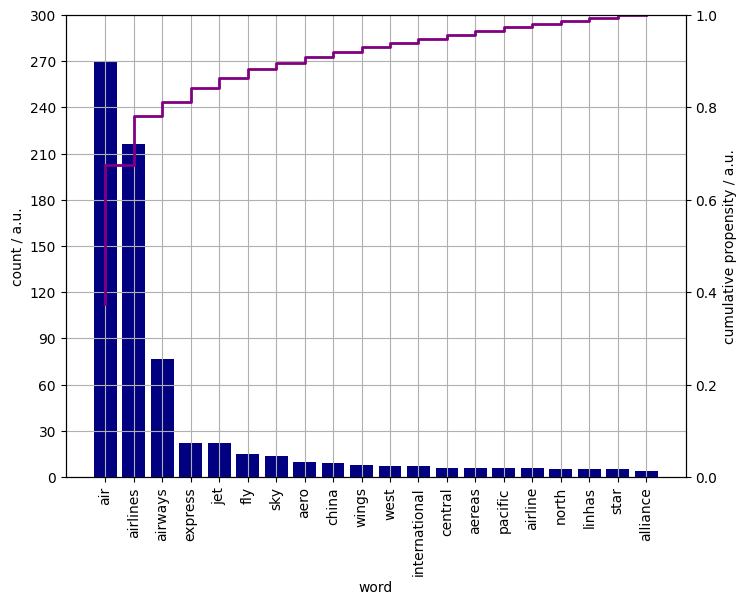

There are a little shy of ten hundred unique airline names (1005). They are composed of approximately eighteen hundred words of which one thousand are different. The twenty most frequent words are shown in Figure 1. The first eight directly refer to air travel, with the exception of express. The words that allude to aviation will be called tokens.

These are

aereas,aero,air,airline,airlines,airway,airways,aviacion,express,fly,jet,sky,wing,wings

Figure 1. The counts of individual words found in airline names (navy histogram). The cumulative propensity thereof (purple line).

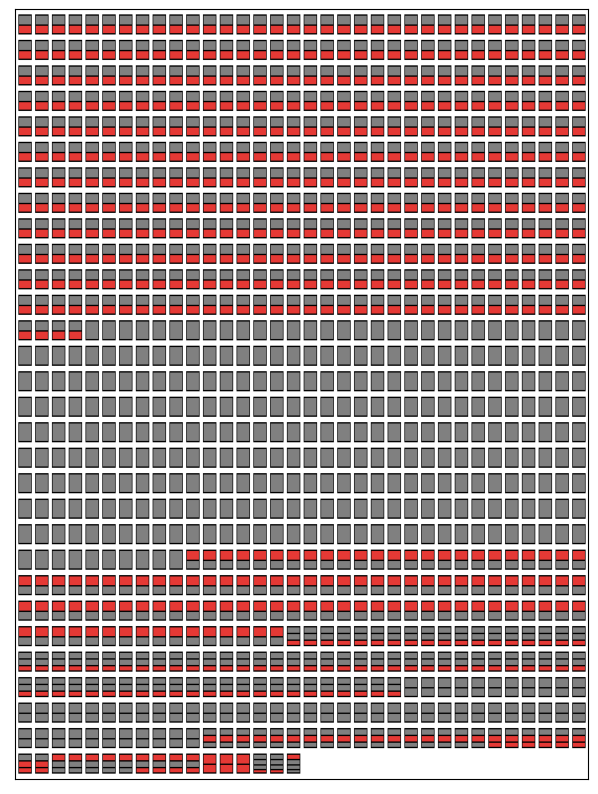

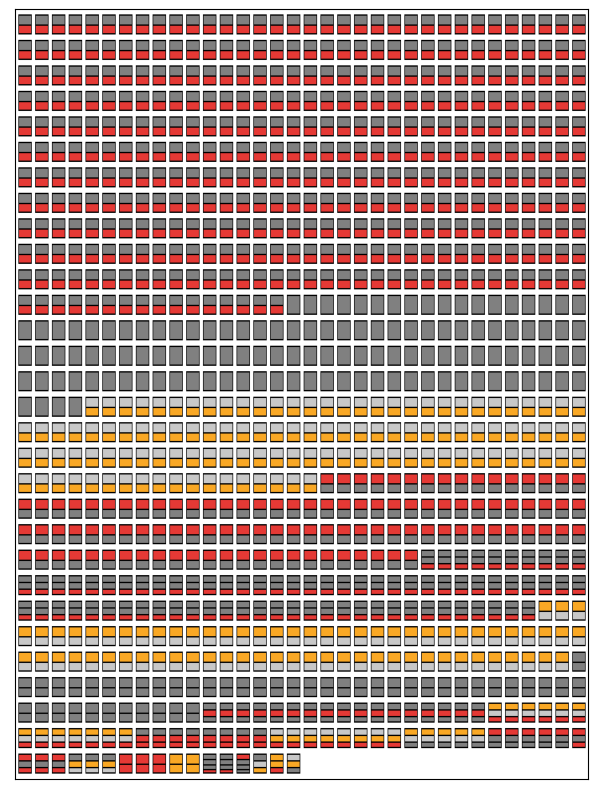

Ninety percent of all words making up the airline names is a token. Assuming that a name can contain at most a single token, about 45% of the names is constructed from one of these seven words. Let us colour the words red if they are a token and dark gray otherwise. By doing so, the entries are transformed to blocks of rectangles as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Airline names represented colour-encoded blocks. Read each stack from top to bottom. Tokens: red rectangles, non-tokens: dark gray rectangles.

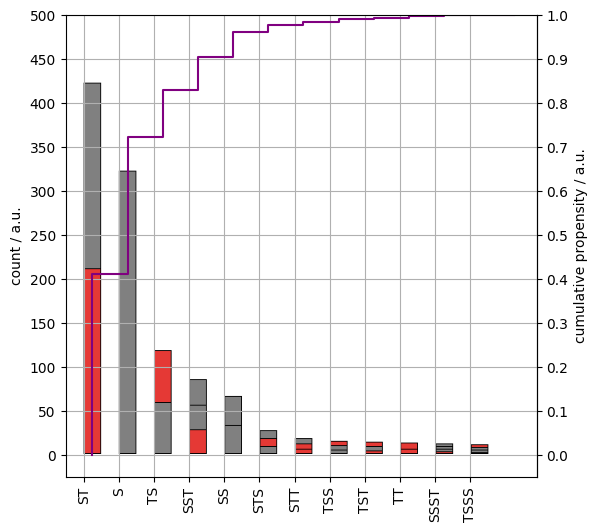

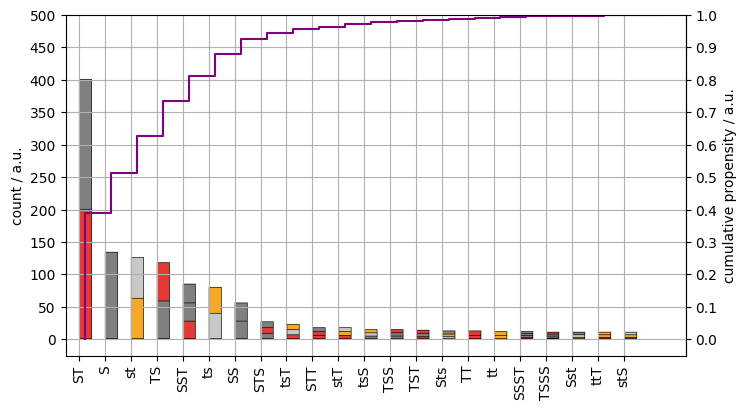

For example, Teapot Airlines becomes a gray shape with a red one underneath it. Each block thus depicts the structure of the name it transforms. If name is a sequence of at most $n$ words then there a $2^{n+1} - 2$ possible structures. We however find that a rather small number of patterns are present as proven by Figure 3. The tokens are denoted by upper case T. All non-token words are represented by an upper case S, in the following. S stands for specifier. A words, for now, which make airline names distinct given a set of tokens.

Figure 3. The counts of airline naming patterns. Read each stack from top to bottom. Tokens: red rectangles, specifiers: dark gray rectangles. Cumulative propensity (purple line).

Roughly eighty percent of the names follow just three patterns:

ST: “British Airways”, “Aegean Airlines”S: “Corsair”, “Eurowings”TS: “Air India”, “Air Inuit”

About one third of all names are not tokens. Still, most of them refer to aviation in their parts. We proceed to locate the fragments related to flying hidden in the non-token words.

Markers

Let us consider the name Corsair. It is clearly composed of two segments. A suffix that refers to aviation air, and a stem that makes the name unique, Cors. If they were separate words, this name would be filed under the category ST. Likewise, Airasia is a connected sequence of a component alluding to air travel, Air followed by a fragment which makes the name unique asia. The word fragments which hint at aviation will be called markers and denoted by lower case t. All other parts of the word will be called specifiers.

Identifying markers

The reader can readily enumerate a handful of markers: air, aero, avia, jet, wing(s). To identify all of them, the entirety of the original list needs to be processed. Given the number of entries, it is best done programatically. A naive solution is to

- iterate over words one-by-one

- form all possible fragments which has a minimum length, say, three

- count all fragments

- the most common fragments will be the markers

This approach would cost us $\mathcal{O}(N \cdot n^{2})$ operations where $N$ is the number of words and $n$ is their mean length i.e. number of letters therein. Strictly speaking, markers are never in medial positions. A word either start or end with them. Still, the word-wise complexity is $\mathcal{O}(n^{2})$ because all subwords need to be checked separately. For example, airasia: air, aira, airas, airasi, airasia

Aside: radix trees

A more performant procedure invokes radix trees. A radix tree is a collated sequence of letters as they appear in a set of words. To construct one

- select all words that start with the same letter

- for all such words

- write down the first letter and increase its count by one

- for all remaining letters

- if the next letter is not in the tree

- draw an arrow to the letter and increase its counter by one

- if the next letter is in the tree

- increase its counter

- if the next letter is not in the tree

The markers are the paths leading to the vertices in the tree where there is a drop in the counter. This solution has the complexity of $\mathcal{O}(N \cdot n)$, for all initial fragments.

Procedure

A two forests of radix trees are constructed. One from the start and one from the end of the words. The tokens are removed beforehand lest they mask the markers due to their sheer proportion. The forests are then processed as follows

- each three is traversed from its root

- paths whose count is above a limit are followed

- if a vertex has many children of small counts it is labelled as a marker

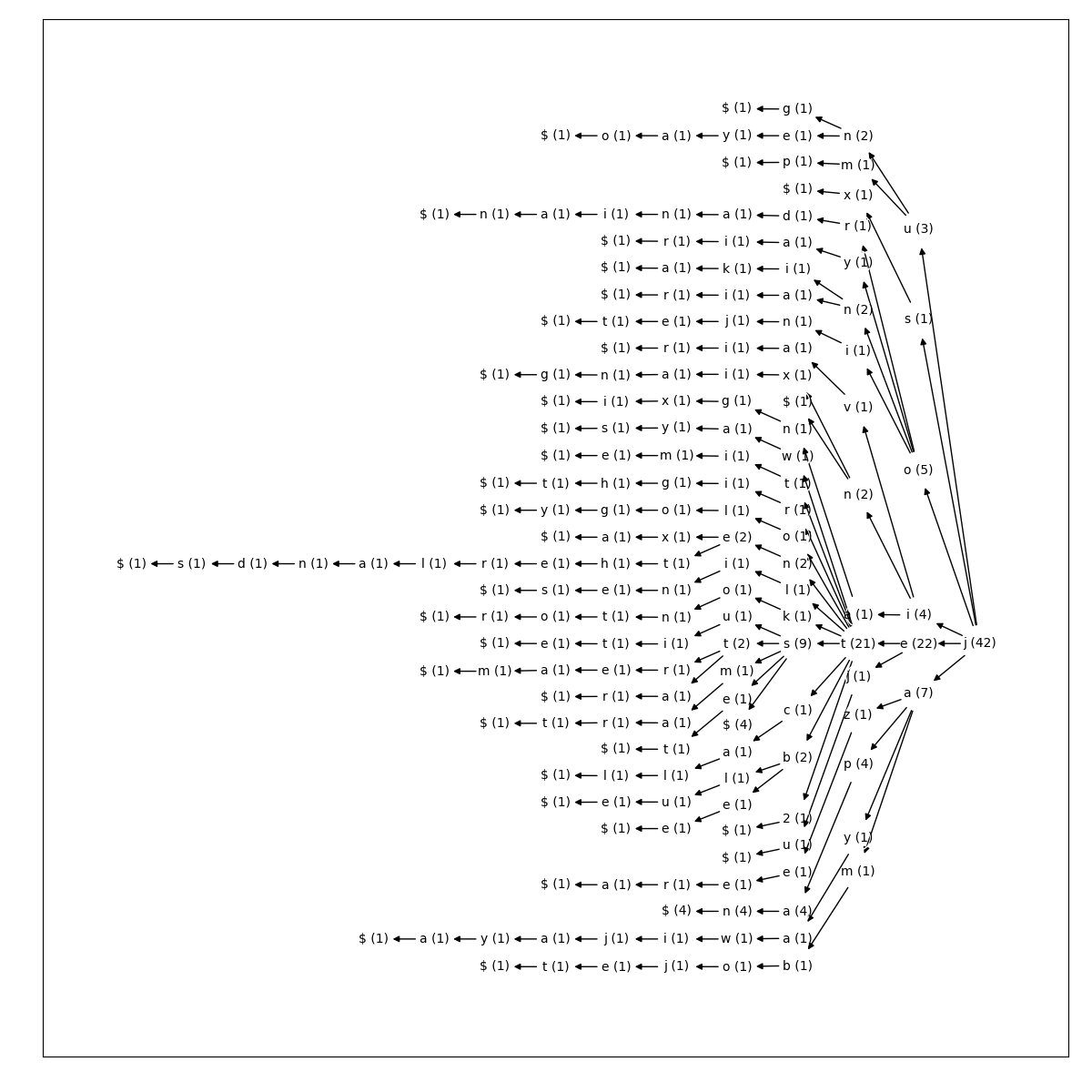

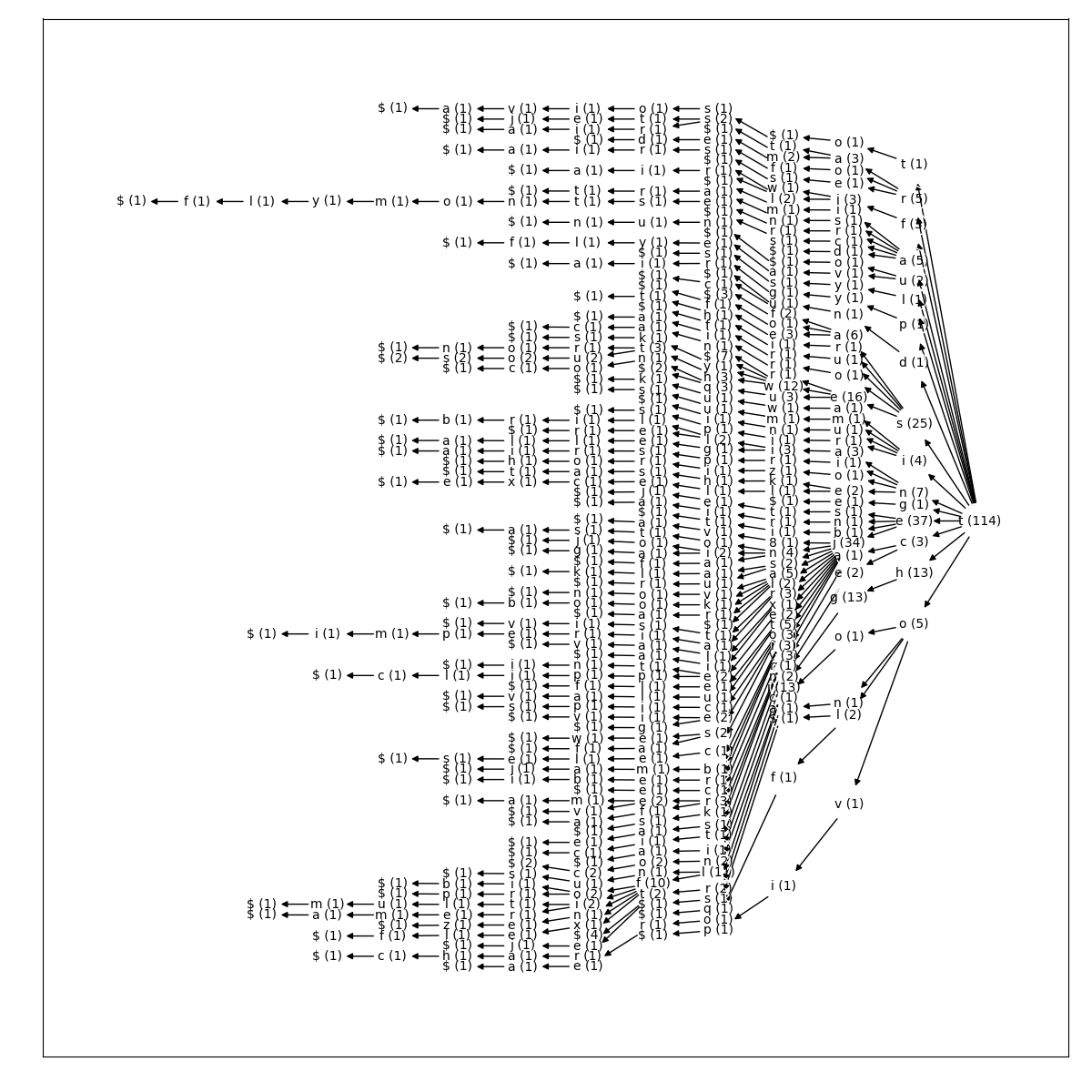

Figure 4. Radix tree rooted at the initial letter j. Counts are in parentheses. Read from left to right to recover the individual words.

Two radix trees which helped indentify the jet marker are shown in Figures 4. and 5. The former plot condenses all words in all names that start with the letter j. There are 42 of the, The most dominant path is j-e-t. It occurs 22 times, it is thus common enough to treat it as a candidate marker. It alludes to the notion of flying, so it is indeed a marker. An example is jet2 which is represented with the code ts.

Figure 5. Radix tree rooted at the final letter t. Counts are in parentheses. Read from right to left to recover the individual words.

The radix trees grown from the end of the words aid us to find the final markers. Figure 5. shows us the counterpart tree used to isolate the marker jet. Each path starts at the end of the words whose last letter is t. The most prominent route through the letters is t-e-j. Reversing it, the component jet is recovered. An example is easyjet which is represented by the code st

The following markers were indentified alltogether:

aero,air,avia,fly,jet,sky,wings

Airline name patterns summary

Having identified the markers and the specifier fragments, more granular naming patterns emerge – twenty two of them. Eighty percent of all names contain at least one reference to air travel. Whole word tokens are four times more prevalent than the markers.

Figure 6. arranges the airline names according to their naming patters. Markers are coloured in orange, fragment specifiers are distinguished by their pale gray shade.

Figure 6. Airline names represented colour-encoded blocks. Read each stack from top to bottom. Tokens: red rectangles, markers: orange rectangles, whole word specifiers: dark gray rectangles, fragment specifiers: light gray rectangles.

The last plot compares the propensities of the detailed patterns. After all, less than 20% of airlines do not refer to their line of business directly in their names based on the figures. There are some false negatives, such as Lufthansa where the luft prefix was not recognised S* < ts. KLM is considered a member of the S pattern. In reality, the L in the abbreviation comes from Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij which would be of StsS class.

Figure 7. The counts of airline naming patterns. Read each stack from top to bottom. Tokens: red rectangles, markers: orange rectangles, whole word specifiers: dark gray rectangles, fragment specifiers: light gray rectangles. Cumulative propensity (purple line).

Finally, an example of each pattern is provided below:

ST:Alaska AirlinesS:Emiratesst:RyanairTS:Air BalticSST:All Nippon Airwaysts:AeroflotSS:Cathay PacificSTS:Delta Air LinestsT:SkyWest ExpressSTT:Caicos Express AirwaysstT:Skyjet AirlinestsS:Skyhigh DominicanaTSS:Air New ZeelandTST:Air India ExpressSts:Iran AirtourTT:Sky Airlinett:Air1AirSSST:Costa Rica Green AirwaysTSSS:Air China Inner MongoliaSst:Malta MedairttT:Skyjet AirlinesstS:Tigerair Taiwan